By Jeff Sessions, United States Senator of Alabama

By Jeff Sessions, United States Senator of Alabama

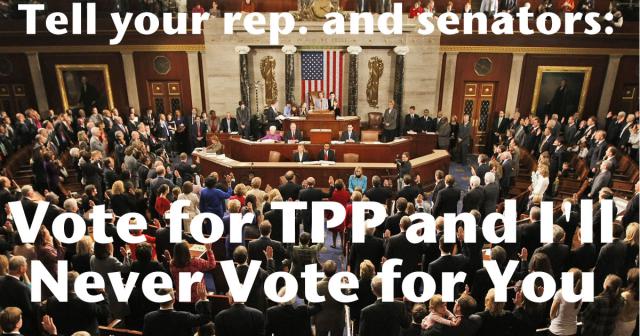

Congress has the responsibility to ensure that any international trade agreement entered into by the United States must serve the national interest, not merely the interests of those crafting the proposal in secret. It must improve the quality of life, the earnings, and the per-capita wealth of everyday working Americans. The sustained long-term loss of middle class jobs and incomes should compel all lawmakers to apply added scrutiny to a “fast-track” procedure wherein Congress would yield its legislative powers and allow the White House to implement one of largest global financial agreements in our history comprising at least 12 nations and nearly 40 percent of the world’s GDP. The request for fast-track also comes at a time when the Administration has established a recurring pattern of sidestepping the law, the Congress, and the Constitution in order to repeal sovereign protections for U.S. workers in deference to favored financial and political allies.

With that in mind, here are the top five concerns about the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) that must be fully understood and addressed before passage:

1. Consolidation Of Power In The Executive Branch. TPA eliminates Congress’ ability to amend or debate trade implementing legislation and guarantees an up-or-down vote on a far-reaching international agreement before that agreement has received any public review. Not only will Congress have given up the 67-vote threshold for a treaty and the 60-vote threshold for important legislation, but will have even given up the opportunity for amendment and the committee review process that both ensure member participation. Crucially, this applies not only to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) but all international trade agreements during the life of the TPA. There is no real check on the expiration of fast-track authority: if Congress does not affirmatively refuse to reauthorize TPA at the end of the defined authorization (2018), the authority is automatically renewed for an additional three years so long as the President requests the extension. And if a trade deal (not just TPP but any trade deal) is submitted to Congress that members believe does not fulfill, or that directly violates, the TPA recommendations or any laws of the United State it is exceptionally difficult for lawmakers to seek legislative redress or remove it from the fast track, as the exit ramp is under the exclusive control of the revenue and Rules committees.

Moreover, while the President is required to submit a report to Congress on the terms of a trade agreement at least 60 days before submitting implementing legislation, the President can classify or otherwise redact information from this report, limiting its value to Congress.

Is TPA designed to protect congressional responsibilities, or to limit Congress’ ability to do its duty?

2. Increased Trade Deficits. Barclays estimates that during the first quarter of this year, the overall U.S. trade deficit will reduce economic growth by .2 percent. History suggests that trade deals set into motion under the 6-year life of TPA could exacerbate our trade imbalance, acting as an impediment to both GDP and wage growth. Labor economist Clyde Prestowitz attributes 60 percent of the U.S.’ 5.7 million manufacturing jobs lost over the last decade to import-driven trade imbalances. And in a recent column for Reuters, a former chief executive officer at AT&T notes that

“since the [NAFTA and South Korea free trade] pacts were implemented, U.S. trade deficits, which drag down economic growth, have soared more than 430 percent with our free-trade partners. In the same period, they’ve declined 11 percent with countries that are not free-trade partners… Obama’s 2011 trade deal with South Korea, which serves as the template for the new Trans-Pacific Partnership, has resulted in a 50 percent jump in the U.S. trade deficit with South Korea in its first two years. This equates to 50,000 U.S. jobs lost.”

Job loss by U.S. workers means reduced consumer demand, less tax revenue flowing into the Treasury, and greater reliance on government assistance programs. It is important that Congress fully understand the impact of this very large trade agreement and to use caution to ensure the interests of the people are protected.

Furthermore, the lack of protections in TPA against foreign subsidies could accelerate our shrinking domestic manufacturing base. We have been getting out-negotiated by our mercantilist trading partners for years, failing to aggressively advance legitimate U.S. interests, but the proponents of TPA have apparently not sought to rectify this problem.

TPA proponents must answer this simple question: will your plan shrink the trade deficit or will it grow it even wider?

3. Ceding Sovereign Authority To International Powers. A USTR outline of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (which TPA would expedite) notes in the “Key Features” summary that the TPP is a “living agreement.” This means the President could update the agreement “as appropriate to address trade issues that emerge in the future as well as new issues that arise with the expansion of the agreement to include new countries.” The “living agreement” provision means that participating nations could both add countries to the TPP without Congress’ approval (like China), and could also change any of the terms of the agreement, including in controversial areas such as the entry of foreign workers and foreign employees. Again: these changes would not be subject to congressional approval.

This has far-reaching implications: the Congressional Research Service reports that if the United States signs on to an international trade agreement, the implementing legislation of that trade agreement (as a law passed later in time) would supersede conflicting federal, state, and local laws. When this occurs, U.S. workers may be subject to a sudden change in tariffs, regulations, or dispute resolution proceedings in international tribunals outside the U.S.

Promoters of TPA should explain why the American people ought to trust the Administration and its foreign partners to revise or rewrite international agreements, or add new members to those agreements, without congressional approval. Does this not represent an abdication of congressional authority?

4. Currency Manipulation. The biggest open secret in the international market is that other countries are devaluing their currencies to artificially lower the price of their exports while artificially raising the price of our exports to them. The result has been a massive bleeding of domestic manufacturing wealth. In fact, currency manipulation can easily dwarf tariffs in its economic impact. A 2014 biannual report from the Treasury Department concluded that the yuan, or renminbi, remained significantly undervalued, yet the Treasury Department failed to designate China as a “currency manipulator.” History suggests this Administration, like those before it, will not stand up to improper currency practices. Currency protections are currently absent from TPA, indicating again that those involved in pushing these trade deals do not wish to see these currency abuses corrected. Therefore, even if currency protections are somehow added into TPA, it is still entirely possible that the Administration could ignore those guidelines and send Congress unamendable trade deals that expose U.S. workers to a surge of underpriced foreign imports. President Obama’s longstanding resistance to meaningful currency legislation is proof he intends to take no action.

The President has repeatedly failed to stand up to currency manipulators. Why should we believe this time will be any different?

5. Immigration Increases. There are numerous ways TPA could facilitate immigration increases above current law—and precious few ways anyone in Congress could stop its happening. For instance: language could be included or added into the TPP, as well as any future trade deal submitted for fast-track consideration in the next 6 years, with the clear intent to facilitate or enable the movement of foreign workers and employees into the United States (including intracompany transfers), and there would be no capacity for lawmakers to strike the offending provision. The Administration could also simply act on its own to negotiate foreign worker increases with foreign trading partners without ever advertising those plans to Congress. In 2011, the United States entered into an agreement with South Korea—never brought before Congress—to increase the duration of L-1 visas (a visa that affords no protections for U.S. workers).

Every year, tens of thousands of foreign guest workers come to the U.S. as part of past trade deals. However, because there is little transparency, estimating an exact figure is difficult. The plain language of TPA provides avenues for the Administration and its trading partners to facilitate the expanded movement of foreign workers into the U.S.—including visitor visas that are used as worker visas. The TPA reads:

“The principal negotiating objective of the United States regarding trade in services is to expand competitive market opportunities for United States services and to obtain fairer and more open conditions of trade, including through utilization of global value chains, by reducing or eliminating barriers to international trade in services… Recognizing that expansion of trade in services generates benefits for all sectors of the economy and facilitates trade.”

This language, and other language in TPA, offers an obvious way for the Administration to expand the number and duration of foreign worker entries under the concept that the movement of foreign workers into U.S. jobs constitutes “trade in services.”

Stating that “TPP contains no change to immigration law” is a semantic rather than a factual argument. Language already present in both TPA and TPP provide the basis for admitting more foreign workers, and for longer periods of time, and language could later be added to TPP or any future trade deal to further increase such admissions.

The President has already subjected American workers to profound wage loss through executive-ordered foreign worker increases on top of existing record immigration levels. Yet, despite these extraordinary actions, the Administration will casually assert that is has merely modernized, clarified, improved, streamlined, and updated immigration rules. Thus, at any point during the 6-year life of TPA, the Administration could send Congress a trade deal—or issue an executive action subsequent to a trade deal as part of its implementation—that increased foreign worker entry into the U.S., all while claiming it has never changed immigration law.

The President has circumvented Congress on immigration with serial regularity. But the TPA would yield new power to the executive to alter admissions while subtracting congressional checks against those actions. This runs contrary to our Founders’ belief, as stated in the Constitution, that immigration should be in the hands of Congress. The Supreme Court has consistently held that the Constitution grants Congress plenary authority over immigration policy. For instance, the Court ruled in Galvan v. Press, 347 U.S. 522, 531 (1954), that “the formulation of policies [pertaining to the entry of immigrants and their right to remain here] is entrusted exclusively to Congress… [This principle] has become about as firmly imbedded in the legislative and judicial issues of our body politic as any aspect of our government.” Granting the President TPA could enable controversial changes or increases to a wide variety of visas—such as the H-1B, B-1, E-1, and L-1—including visas that confer foreign nationals with a pathway to a green card and thus citizenship.

Future trade deals could also have the possible effect of preventing Congress from reforming abuses in our guest worker programs, as countries could complain that limitations on foreign worker travel constituted a trade barrier requiring adjudication by an international body.

The TPP also includes an entire chapter on “Temporary Entry” that applies to all parties and that affects U.S. immigration law. Additionally, the Temporary Entry chapter creates a separate negotiating group, explicitly contemplating that the parties to the TPP will revisit temporary entry at some point in the future for the specific purpose of making changes to this chapter—after Congress would have already approved the TPP. This possibility grows more acute given that TPP is a “living agreement” that can be altered without Congress.

Proponents of TPA should be required to answer this question: if you are confident that TPA would not enable any immigration actions between now and its 2021 expiration, why not include ironclad enforcement language to reverse any such presidential action?

CONCLUSION

Our government must defend the legitimate interests of American workers and American manufacturing on the world stage. The time when this nation can suffer the loss of a single job as a result of a poor trade agreement is over.

The American people want us to slow down a bit. The rapid pace of immigration and globalization has placed enormous pressures on working Americans. Lower-cost labor and lower-cost goods from countries with less per-person wealth have rushed into our marketplace, lowering American wages and employment. The public has grown increasingly skeptical of these elaborate proposals, stitched together in secret, and rushed to passage on the solemn promises of their promoters. Too often, these schemes collapse under their own weight. Our job is to raise our own standard of living here in America, not to lower our standard of living to achieve greater parity with the rest of the world. If we want an international trade deal that advances the interests of our own people, then perhaps we don’t need a “fast-track” but a regular track: where the President sends us any proposal he deems worthy and we review it on its own merits.

Source: Jeff Sessions, Alabama Senator